|

Tom McCarthy: If I had to describe what your remarkably diverse body, or bodies, of work is about, I think I'd use the word 'transformation'. It's about transformation of places and identities, of intellectual disciplines, bodies of knowledge, histories -- just endless transformation. Now I know that your influences -- or, better to say, the philosophical texts that you move through and use to transform yourself -- are as diverse as the subjects that your work deals with. But I still wonder whether there are some ideas or thinkers that together form a sort of source code. Maybe people like Heraclitus, or Ovid, or The Book of Changes, or maybe something else entirely. So my first question is: if we had to do an archaeological dig of Perryville, what might we find among the foundations?

Paul Perry: Do you really see it as being so diverse? So eclectic?

TMcC: Yes. One minute we're in Aristotle's Poetics, and the next we're off in some Eastern text, or film history, or a technical, scientific area. And these are not just glanced at: these are fields that you've clearly 'got', downloaded as it were.

PP: I'm interested in all these things.

TMcC: But is there one privileged set?

PP: There isn't really a single piece of code, a single codex. Maybe my work's a search for that codex. I've always been sort of hungry; I also have a short attention span. I suspect I have an Attention Deficiency Disorder. I think I've had it since I was a child.

TMcC: Maybe ADD's a good thing, in that it encourages eclecticism.

PP: Yes, totally. I also think I'm really lucky to live now, in a time where I'm able to externalise my memory, because it allows me to stand on my own shoulders. I'm a bit like a comet that flies back to certain interests on a regular basis. The nice thing about externalised memory is that you can pick up a subject where you left off. That's the incredible affordance of computers: being able to archive and store one's own information.

TMcC: You have an enormous web presence.

PP: Yes, it's getting there. The intention when I began the weblog was to do it for the rest of my life. I've been doing it for three years now, and it's slowly becoming more interesting. I search it myself all the time. I'm thinking about something, and then I remember that I wrote something about it a year or two ago but I can't remember what. This poses an interesting problem: the more you externalise things the less you can recall them yourself. But I'm finding this frees you up. As long as you know where you stored it, the address. I find it very interesting to be able to search your own memory archive.

TMcC: Lots of people have websites, but they usually remain external to them. With yours, though, the internal/external thing becomes blurred. You put your diary up there; you put correspondence and books you've read. You write letters to yourself a year into the future, or the past, depending on when you're looking from. It's almost as though you've transferred yourself wholly into the medium, leapt into it like the hero in Tron leaping into the computer. So a vital question for me at this point becomes -- and I don't mean this in a prying, personal way, but rather in a real ontological sense -- what's left out? What remains?

PP: Everything. One becomes more aware of the public and the private. I'm really a super-private person. I spend long periods of time alone. I have friends I'm very close to, but I don't know that many people. Another friend of mine is doing a similar project, and he put it most beautifully: 'I cherish my hesitation about what to publish and what not.' For me, the project began out of two kinds of thinking: I was running a master's program for artists who wanted to work with new media. I don't consider myself a new media artist; I'm trained as a sculptor, and that's what I do. But I spend a lot of time online. So at the time I was working with students and they were all making interesting websites. So I wondered what type of site I might make myself. Then I started making small sites for different projects. It was basically to organise information: I was working with different people all over Holland, running from one place to the next, and I found I kept losing track of what I'd said to whom. I was interested in Goldhaber's work on the attention economy. So I started making little sites for the classes I was working with, with sets of links. But after a while I got fed up with this and decided I just wanted one site: one site for the rest of my life, for everything -- one site to fit all. It came largely from Goldhaber's ideas.

TMcC: What does he say?

PP: He says it's ridiculous to talk about an information economy, because information isn't limited. You can't have an economy of something that's unlimited. Goldhaber points out that what we do have a limit on is the amount of attention we have, and how much we can give. We have a finite number of waking hours, and if I'm paying attention to you now then I can't pay attention to someone else or to what's happening outside. The give-and-take of attention can be understood as an economy. I found this very interesting and, as I live a life where I do one thing and then another, pick up this book and then that book, look at this and then that, I wanted to keep a record of the things I pay attention to. That's how it began: keeping a log of my attention.

TMcC: And networking it all together.

PP: Yes: working it all into one, a basic desire to try to tie all the interests together. A website is quite arbitrary, because actually one page is as close to the next as to any other on the net; but it just feels more together.

TMcC: And there's the umbrella of the proper name...

PP: Yes, that's a good way of putting it.

TMcC: Talking of proper names: the title of your domain is 'alamut'. It's a very loaded term.

PP: Sometimes I'm really sorry I chose it. It can attract the wrong type of attention.

TMcC: Let's remind ourselves what the origins of the name are.

PP: You tell me.

TMcC: Alamut was the mountain fortress of Hasan-i Sabbah, who lent his name to the hashishins, the assassins.

PP: Yes. And he was able to maintain his autonomy, or his group was, for several hundred years. No one fucked with them -- basically because they were practising an early form of information warfare, I think.

TMcC: You see them as a model of autonomy and temporary autonomous zones, whereas I see them as the perfect model of control and control systems. In Marco Polo's version at least, they had this elaborate trick whereby they'd lure young men away from villages, dose them up with loads of hashish and then take them to...

PP: The garden of pleasure...

TMcC: Yes, this sort of film set, fake film set, where there was wine gushing and maidens giving them blow jobs or whatever, and the 'voice of god' rigged up through a primitive PA saying: 'You must follow my one true prophet Hasan-i Sabbah.' So the reason it was such a strong cult was that the young men believed that Hasan-i Sabbah was God's true prophet and if they died they'd go to heaven. So I saw that as the perfect model for corrupt modern democracies: the rulers induce belief in others while not in fact believing themselves -- they make people believe in the democratic process in order to advance their own concerns.

(Off stage: Osama bin Laden, the 'Old Man of the Mountain')

PP: I have an archive of different takes on the situation. I've even been getting gifts, like a videotape from a Swedish artist who made a trip to Alamut in the eighties. There's no fortress left today; it's just a rocky mountain top. But the breaking of the chains of the law, that's what it is about: 'Nothing is true, everything is permitted'. That was Hasan-i Sabbah's credo. The situation at Alamut maps across many others. I have this picture of Bin Laden sitting in his cave fortress: to me he's the modern Hasan-i Sabbah. I first came across the 'Old Man of the Mountain' through Burroughs and the anarchist cum Islamic Scholar, Peter Lambourn Wilson, aka Hakim Bey, author of The Temporary Autonomous Zone.

TMcC: He writes about the internet too, doesn't he? He describes it as a 'psychic slum haunted by ascended Heaven's Gate masters and prisoners in Texas doing data entry'.

PP: Yes, he's not much of a technophile. But through reading him I became interested in different aspects of this place Alamut. I was using the name in other contexts before I registered it as an online domain.

TMcC: You did an artwork in Vilnius, didn't you, that was based on the idea of Alamut? It involved a sheep...

(Off stage: The lion lies down with the artist. Vilnius 1995.)

PP: A lion and a lamb. I did a series of projects called Temporary Autonomous Zoo. One thing I was looking at was the difference between zoos and museums. One stores and preserves our cultural heritage, the other our biological heritage. The trouble is we still see the zoo as operating within an entertainment paradigm. The San Diego Zoo, for example, has an enormous frozen, or cryonic, zoo, and many zoos are doing important conservation work, but we still have this problem: we don't like seeing animals behind bars, we can't recognise that if they're not behind those bars, they're nowhere. So I was interested in museology, and wrote a text once about collecting and the history of showing things, from Wunderkamers onwards. Alamut is very much my private Wunderkamer.

TMcC: So in Vilnius...

(On stage: Movable Observation Post, High View Point. 1993.)

PP: There was a series of works I did with Jouke Kleerebezem, a colleague. One was Movable Observation Post, High View Point. It was a bird blind. Early bird blinds were made to look like natural entities, models of cows and things; so we got this notion of camouflage, cultural and biological camouflage, and we created two lifesize giraffes with real giraffe skins and bones and bits of Desert Storm camouflage, meant for birdwatching. Then we were asked to make a show in Vilnius. I'd had this dream to do something around the phrase 'When the lion lies down with the lamb.' The local zoo lent us a baby lion, so we made a piece with lion and lamb together.

TMcC: So what did they do together? Lie down?

PP: Sort of. We had this young girl who was with them the whole time. The lion was playing to kill. There was a containment created from baby beds, from thirty or forty wooden cribs, a double wall. We did the piece at a time in Lithuania when everything was needed, so we could give the cribs to a baby hospital afterwards.

TMcC: Was this at the time Lithuania was splitting?

PP: Just after.

TMcC: So there's a big political metaphor there: they're the lamb and the Soviet Union is the lion.

PP: Hmm. Sort of. On the side of the containment we constructed a flat castle tower, a wooden framework covered with the cardboard in which the beds had been shipped from Holland, and on it we painted a text, an Alamut-like text: 'If heaven is on earth it is here, it is here.' In English and Lithuanian.

TMcC: After that you did another work that also had a heaven on earth/garden of pleasure/temporary autonomous zone theme: your 1997 piece A Model Garden for Two Cars.

(Study: A Model Garden for 2 Cars. 1997.)

PP: It was a study commissioned by Flevoland, the newest province of Holland. One of the last major earthworks in Holland was the closing off of the Zuiderzee with the Afsluitdijk to create the Ijsselmeer: from the Ijsselmeer the Dutch created an entire province, after the war, of land reclaimed from the sea. In the nineteenth century the Zuiderzee contained islands with little fishing communities on them that were constantly in danger of starving; now they're just tiny bumps in a flat landscape. In the seventies there were a number of major land artists, like Smithson, who were inspired by the Dutch landscape and who did projects in Holland.

TMcC: What did Smithson do?

PP: He did something similar to his spiral jetty: a spiral hill in a quarry. The Dutch have always been interested in land art, they're fond of saying "God created the Earth but the Dutchman created Holland." So in the nineties this new province commissioned a number of artists to think of new land art projects. That was the context for A Model Garden for Two Cars. I created a temporary autonomous parking lot with two cars. I grew up on the West Coast of Canada, and out there there's a lot of heavily logged forests. The last few years I've been going back to look at property to buy. I've seen several that had been clear-cut.

TMcC: Razed?

(Study: Clear-cut forest.)

PP: Yes. I found them incredibly beautiful. And so my idea was to have a parking lot garden, to bring the two types of space together. The model I made contained the stumps of forty clear-cut trees. Another, earlier, idea was to do a cultigen garden.

TMcC: What's that?

PP: Cultigens are plants which can no longer replicate themselves without man's help. The idea was to have a garden where all the plant material was totally dependent on human intervention.

TMcC: What I really like in that project is that you're dealing with issues around ecology, but you haven't fallen into naturalist fallacies. It reminded me of the anti-naturalism of Joris-Karl Huysmans' Against Nature. Were you thinking of that?

PP: No, but I like that book. Especially the chapter with the jewel-studded tortoise.

TMcC: He gets all these plants cultivated: first fake plants, then real plants that look fake, and ones that simulate disease. So he's sort of trashing, in a sophisticated way, this ecologist tradition, which if you look into it is quite bound up with extreme right-wing discourses. Our notion of nature is a construct, to say the very least. And I like the way your project deals with nature in a way that foregrounds artifice.

PP: You know the oldest cultigens are psychotropic plants from the Amazon rainforest. They appear to have been human-bred already for thousands of years, engineered so far that they can no longer replicate themselves without man.

TMcC: But what drew you to the idea of the parking lot? The artist Ed Ruscha has got into those recently, too. Is it geometry?

PP: I don't know. I was looking at runways for aircraft. I'm quite a materialist, and asphalt is quite a sensual material. I like how it smells when it's hot, that kind of thing.

TMcC: The same year, 1997, you did this enormous project Good and Evil in the Long Voyage. It's a very technical work. You're not just using science as a metaphor: you're actually doing it as well.

PP: I was involved in actually doing it, yes.

TMcC: So could you explain how you went about setting up and executing that project?

PP: I live in Holland, and Holland is an excellent place for doing this sort of work. Two women, who live in Maastricht and do projects every couple of years funded by the Mondriaan Stichting, were doing a project called '(P)reservations'. They invited Mark Dion, Henrik Hakansson, Mike Tyler and a number of other artists who work with biological systems, including myself. The husband of one of the organisors is also the head of pharmacology at the university hospital in Maastricht, so they invited the artists to come and visit the hospital a year ahead and see if we could work with people from the hospital. I got really lucky there. I was interested in what created difference at the cellular level. I'd read about a technique called Inter-Cytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI), which is when they inject a human sperm inside a human egg to help it fertilise the egg. I wrote a little essay called 'Genesis Barrier', and started talks with the hospital.

TMcC: The idea being that you'd inject one of your sperm...

PP: Into a sea-urchin egg. The study of embryology began with sea-urchins. They have very large eggs. So I was linked up with this major molecular cell biologist and we started talking. The hospital was a bit worried because ICSI is a very controversial area. There were twenty or thirty couples who'd been waiting years to try it but the use of the technique raised a lot of questions. I felt that if I used the technique for my own purposes it might draw adverse media attention and hinder the couple's chances. So the biologist came back to me with another suggestion: he asked me if I knew what a hybridoma was.

TMcC: A hybridoma?

(Preparation: Taking blood.)

PP: A hybridoma. I didn't know, so went away and spent two months reading about it. Basically, there's a way to fuse two different kinds of cell together, usually mouse-mouse. That is: two different types of mouse cell are fused to form a new cell. They do this for research purposes, in order to create what are known as 'immortal cells', cells that won't die when cultured. They take a particular cell from a mouse, a special sort of cancer cell, and fuse it with a target cell, say a liver cell. The cancer is a very specific cancer. Actually it's a cancer because the cells don't die as they normally would. Immortal cells were first found in a black woman, named Henrietta Lacks, who lived in Baltimore in 50's. She was sick, went to the hospital where they took swabs and found she had cancer; she died six weeks later. This would have been the end of her story except they found that her particular cancer cells, from the cultures they took, did not die. Those cells are still used today to do cancer research. But there was a scandal. A journalist wrote a book about it in the eighties called A Conspiracy of Cells. Essentially, the hospital never informed her family; the family only found out ten or fifteen years later that this woman's cells were spread over the entire globe, still propagating. By virtue of her immortal cells she had become the universal mother of cancer research.

TMcC: Cells normally die when cultured, right?

PP: Right. There's something called the Hayflick limit, which dictates that a normal cell can only replicate so many times, and then it dies.

TMcC: So a hybridoma overcomes this limit?

PP: Yes. We took a myeloma from a mouse and fused it with one of my white blood cells, a lymphocyte. It took millions of attempts to achieve a single success, but it worked. As far as we know it's never been done before.

TMcC: All of this is taking place at a very microscopic level. How did you render it visible as a work of art?

(On stage: Good and Evil on the Long Voyage. 1997.)

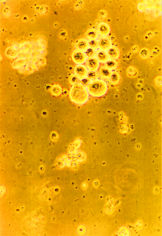

PP: Material is very important for me. I'm interested in the real thing, in the presence of the real thing. I wanted to have the actual cell culture present in the exhibition. This was somewhat complicated. The culture must be kept in a bioreactor, an extremely expensive device. I was able to get one on loan from New Brunswick Scientific. For the exhibition we put the bioreactor in a canoe and lofted it up in the air in a scaffold. The scaffold continued up past the canoe and held a very large mirror at a forty-five degree angle to the floor. So you could stand beneath it, look up and see the bioreactor. You have to think of a bioreactor as an intensive care unit for a cell culture. At the center of this one there was a small flask of pinkish liquid being stirred by a magnetic stirrer, and in that flask the transgene cell culture which was half-me, half-mouse. And on the wall I fastened a very small photo of the replicating half artist - half mouse cells.

("And on the wall I fastened a very small photo...")

Rob la Frenais: Where did you take your cells from?

PP: They were white blood cells, lymphocytes. The common conception of white blood cells is that they are soldiers, protecting us, taking out whatever invades our body. So the white blood cell was the good and the cancer was the evil, and immortally fused together they were on the long voyage.

TMcC: And the canoe was tapping into Egyptian and Greek symbolism...

PP: And native North American. That's still strong for me.

TMcC: I like the analogy you draw when discussing this problem of rendering visible something that's taking place at an invisible level. You talk about phenotype and genotype. The genotype is the information...

PP: Yes, and the phenotype is the expression of that information. It applies to all art.

TMcC: Your next major piece is Amsterdam 2.0. This project seems to be about mapping and inhabiting space, but more essentially about transforming it -- again, transformation. What were the main 'drivers' there for you?

PP: Again, it was a beautifully Dutch-afforded project. It's had a number of iterations. And again it began as a Mondriaan Stichting project. A photographer, an architect and myself were brought together and asked if we would set up a shadow city planning office in Amsterdam, to write and develop scenarios for the future of the city. We called it 'Amsterdam 2.0'. We were paid to meet for two or three days a week for six months, and given an office and a budget so we could invite people to come and talk to us -- a little like what you're doing here. We each had a different interest. I was interested in anarcho-capitalism, and specifically something called poly-centric law. To cut a long story short, I developed a constitution for the future of Amsterdam. The constitution is a framework for a city that is radically tolerant, that in fact is more like a country than a city in that it contains cities: an enormous number of cities without territory, the 'real' cities of Amsterdam 2.0. Each of these daughter cities distinguishing themselves by their difference. What Bruce Sterling calls experiments in living. I personally feel diversity is the most important thing in the world, and I don't see it much in our present society. Warhol's MacDonalds monoculture is the order of the day. He once said that the most beautiful thing about Tokyo is its MacDonalds.

TMcC: Yes -- and that Stockholm didn't have anything beautiful yet.

PP: Exactly. The net is affording an explosion of diversification. People are able to develop their special interests and build communities around those interests. Amsterdam 2.0 could have neo-fascist elements, could have anything. I spent a long time looking at Amsterdam's role in seventeenth century Holland, and then at Amsterdam today as a Mecca of sex and drugs. Amsterdam doesn't like to think of itself this way, but that's the rest of the world's perception of it. I looked at the inside and outside of Amsterdam, and how Amsterdammers themselves perceive their city. The whole project was about thinking of ways to extrapolate Amsterdam's history into the future. Holland is all about space: about planning and managing a tiny space. I don't think there's anywhere else in the world where's there's so much rhetoric around dividing up a few square metres. The Randstad cities -- Amsterdam, Utrecht, Rotterdam and the Hague -- are all the same, are fusing together into a supercity. Talking to business people, I learned that today every good business plan contains a franchise clause. So I thought: well, why not franchise Amsterdam 2.0?

("The most elegant games have only a few rules...")

TMcC: A distinguishing feature of any normal city is its stasis: it is where it is and you can't just move it somewhere else, unless you're in Calvino's Invisible Cities. But your reconstituted Amsterdam is built around possibilities of movement. You even write somewhere: 'Amsterdam 2.0 is about the survival of those who travel furthest.' If I've understood it rightly, you can 'be' in Amsterdam 2.0 in numerous different places.

PP: Anywhere, yes.

TMcC: How does that actually work?

PP: I subscribe to the theory of polycentric law: the idea that law can be separated from jurisdiction. Jurisdiction is about geographical territory. We see more and more problems here: the fatwa against Rushdie, or people being extradited, pulled off aeroplanes. I understand US law enforcement agents often go over the border into Mexico, kidnap people and pull them back.

TMcC: There's the Lockerbie trial in Holland right now, with this little enclave of Scottish law being set up on Dutch soil.

PP: Or you've got these people who publish on the net stuff that's legal where they're doing it but not elsewhere. So it's legal, say, in one state of America, but when they travel to another they're arrested. There was a paper published in the nineties called The Coming Swamp of Global Jurisdiction. I believe that, like insurance, law will eventually be privatised. All the different legal systems will operate under agreement: having apriori worked out what to do in various situations. With the constitution of Amsterdam 2.0, I wanted to make it so that you and I could be living next door to each other, but you could be subscribed to a legal system where murder was a capital offence whereas I'd be subscribed to a legal system where it was simply a misdemeanor. And we could be neighbors, you living in one city and me in another.

TMcC: I've read your constitution. It's very detailed. You follow the precise forms of a constitutional document. It's quite a boring document in a way -- in the way that all official documents are.

PP: I consulted a lot of constitutions. You can read all the world's constitutions online. There are also people writing fictional constitutions for imaginary countries. My constitution is based on an Icelandic constitution from the twelveth century -- and on Amsterdam's past. Law is interesting. It's fun to see how simple rules can breed both complexity and elegant solutions. While researching the constitution I once again became fascinated by games. The most elegant games have only a few rules: they're very simple, but they afford extraordinary complexity. One provocative aspect of my consitution is its suggestion that Amsterdam secede from the rest of the Netherlands: actually float away. Holland in the past has experienced an extraordinary diaspora: the Dutch were here, there, everywhere. You've talked to me a little about your INS project; the fact that it's being situated in this particular space, the Austrian Cultural Institute, means it indirectly addresses some of the same issues.

TMcC: For sure.

PP: Sometimes I think: why not encourage the Dutch to leave Holland? They did it once, they can do it again. As a matter of fact you see it happening again on a small scale: I know Dutch people who've moved abroad but remain Hollanders. Expatriates. I've lived in Holland nineteen years, but I still feel very much Canadian.

TMcC: There's the question of the status of your consitution. My organisation has faced this with our manifesto: some people want to treat it as conceptual art and others, mainly retarded journalists, want to run photo-features on our 'craft', our vehicle for entering death, which they probably imagine as a bunch of cardboard boxes and old television sets hammered together or something. Well, I wonder: would you call your constitution a parody? Or a pastiche? Or a straight-up consitutional document?

PP: The last.

TMcC: Did you take it out of the art realm into the civic realm? Did you show it to town planners?

PP: Yes.

TMcC: What was their reaction?

PP: The second iteration of the project, during which I actually presented the constitution (we're going into the third iteration now) was funded by the Dutch Stimuleringsfonds voor de Architectuur, the National Fund for Architecture.

TMcC: At one point you list all the books in the state library of the reconstituted Amsterdam. I found it very interesting that Aristotle's Poetics is in there but not Plato's Republic.

PP: That wasn't the state library; it was just the list of things I'd been reading and using. I'm a dilettante. I was reading Jane Jacobs too. An interesting urbanologist. And Kevin Lynch.

TMcC: I thought maybe the omission of Plato was a rejection of his decision to exclude poets from his city state. He says: 'We'll deck them in flowers, and then kick them out.'

PP: Nice, but no, that wasn't it. But there's also another part, that we're going into now, where I named four hundred cities that would be part of Amsterdam 2.0. The idea is to develop these daughter-cities and daughter-constitutions, and flesh them out a bit. We're looking at ways of doing that now.

TMcC: Last time I met you you were embarking on a new work called A Thousand Deaths: Sortie 1. Where's that got to?

PP: Can I go back to your first question first?

TMcC: Of course.

PP: You wondered what lay at the bottom of Perryville and I've been thinking about it. What ties this seeming eclecticism all together is an interest in identity. That's what it's all about. I began as a sculptor making art for the artworld, museum/gallery-oriented things, objects of desire and so on. I never thought about public space. That is, until I was approached by the Praktijkburo, an organisation that has now become part of the Mondriaan Stichting, an advice bureau for cities and organisations that want to do large projects in the public sphere. They sometimes invite artists from completely outside the 'public art' discourse. They invited me in '90 or '91 to submit a proposal, I wrote an essay about representing the identity of a group of people. I'd never really thought along those lines before, but this started me off. Then in '91-92 I made a work called Victory - Love - Conquest: a Monument to Rape. In it I was trying to understand Will to Power, man's drive to push the envelope, to conquer new worlds. Over the last few years I've begun to rethink that as Will to Space, and then even more recently as Will to Identity. So many things can be explained from the perspective of identity seeking. So that's the answer to your first question. And the final project, A Thousand Deaths is really about that. And it's certainally about necronautics. You want to know where the new work has taken me? I injected myself with a drug, ketamine, to have a near death experience...

(Victory - Love - Conquest: a Monument to Rape. 1992.)

TMcC: Doesn't ketamine induce hallucination?

PP: It's an anaesthetic. But it has different properties at different dosages: emergent properties. To be clear: I injected a very specific dose that induces a psychological effect very similar to a near death experience.

TMcC: Entering the tunnel and so on?

PP: Yes. But as a matter of fact there is no categorical NDE. There are perhaps twenty or thirty possible features, of which any single NDE will only have five or six.

TMcC: You contacted the INS's techno-chemical division, and through them made contact with a scientist who's written widely about this...

PP: Karl Jansen, yes. He's done it himself too. He claims hundreds of times.

TMcC: So if the genotype of that project was your experience on ketamine, what was the phenotype?

PP: It began in a simple way: last summer I was thinking about the experience economy -- another economy. And the question popped into my head: in an experience economy, what would be the value of a near death experience? I didn't know anything about the subject then, so I started looking, and was shocked to find that near death experiences warrant a whole category on Amazon: hundreds of books are dedicated to the subject. But it stands to reason, there's an incredible desire to know what comes after this: ninety-nine percent of books on NDEs use the experience to try to prove that there's some kind of afterlife. I am not a believer. The only person I think has dealt with the subject well is Susan Blackmore in her book Dying to Live: Near Death Experiences. The same Blackmore by the way who wrote The Meme Machine.

TMcC: What's her take on it?

PP: She invokes Occam's Razor: you don't need to bring in all sorts of external beliefs to explain the phenomena. More and more people are having NDEs because more and more people are brought back from death's door after medical intervention. She feels all the accounts are explainable in terms of the body shutting down. But she does concede -- and this is interesting -- that the experience fundamentally changes the life of a significant percentage of people who undergo it. Everything changes. As far as I know, there is only one writer who's done any sort of theory-forming about this, and that's an Australian psychiatrist named John Wren. He had an NDE himself in Thailand in the eighties, and has been trying to work out what happened ever since. He talks about the death of the 'hyperactive survivor mechanism'. So that started me thinking: what would be the value, in an experience economy, of this type of thing if you could on-demand it?

TMcC: As you've been talking about all these economies and all these spaces and anarcho-capitalism's relation to space and so on, it's occurred to me that when you look at the history of Amsterdam you're looking at the history of capitalism.

PP: It is totally the history of capitalism.

TMcC: And the miracle of capitalism is that it's all about the gap, the speculative gap. It's like the fort-da game, in which Freud's grandson reenacts the death and disappearance of his mother by throwing away a toy so that he'll get it back again later. It's not about straight exchange, but rather about loss: you give things away in the hope that you'll get more back in the future. That's what speculation is about.

PP: And risk, and insurance. All these things begin in Amsterdam.

TMcC: Exactly. So in capitalism value and exchange revolve around the opposite of value: they're actually grounded in absence, in continual loss. That's what investment is: losing in the hope of future gain. With the death thing it's the same: death is the opposite of experience, so that makes it the essential element, the sine qua non of an experience economy.

PP: My project is about surviving death, really. There's a bit in the film, an intertitle actually, that says: 'If death be a mirror in which the meaning of life is reflected, then the Near Death Experience is a short excursion through that looking glass and back again.'

TMcC: Like Cocteau's Orphée.

PP: Or Alice in Wonderland.

(Study: Entering and leaving.)

TMcC: So A Thousand Deaths: Sortie 1 consisted of you injecting yourself with ketamine in order to induce a near death experience. If that was the genotype, the phenotype was filming it, right?

PP: I guess. We worked with a small crew. We had actors too.

TMcC: What were they doing?

PP: From the moment I conceived of the project I knew I wanted to do it a number of times. I really hope to be able to continue this for the next couple of years. So the first film was a bit like an introduction. I really like the idea of the performances made on parabolic flights, theatre or dance pieces that are constructed from several parts, with intermissions between. I liked this idea of dipping in and dipping out: a sortie. You've done it, right, Rob?

RlaF: Yes. You get thirty seconds of zero gravity at a time.

TMcC: And you do it eight or nine times?

RlaF: Last time we were meant to do fifteen but had to stop after twelve because somebody got ill.

(On stage: A Thousand Deaths: Sortie 1. 2000.)

TMcC: Sortie is a military term, isn't it? You make a sortie from your encampment.

PP: It just means exit. A Thousand Exits. If I could go back to your opening question once more: there are two codexes to what I do, in fact. One is the work of Gregory Bateson. He was a systems theorist. He was born around the turn of the century, and died in nineteen eighty or so. He moved from field to field. He did a lot of early work in anthropology, founded the notion of visual anthropology, then in psychiatry, psychiatric hospitals, developed an interesting theory of schizophrenia. His father was a famous nineteenth century biologist. Gregory wrote a collection of essays called Steps to an Ecology of Mind. As a matter of fact I have everything he wrote. He advances a form of pattern-thinking which I suppose totally informs my own thinking. He has this great definition of information as 'the difference that makes a difference'. The other influence on my work, especially on A Thousand Deaths is Buddhist philosophy and psychology.

TMcC: There's a fascinating link on your website to two Westerners interviewing the Dalai Lama, asking him if a scientist could be reincarnated as a computer.

PP: Francisco Varela, yes.

TMcC: You have another link to the Extropians site. These are people trying to overcome death by freezing or uploading themselves. It seems to me that these people don't in fact have a relationship to death. They want to totally clear death out of the way, deny its existence. I see it as totalitarian, almost fascistic. Also, they're so humourless! But what's your impression of them?

PP: I actually admire them. All life is premised on death; evolution is premised on death. But their work raises the question: what would happen if we had hundreds of years? Would that change the pacing? I believe the pacing's changed already, in terms of how people live. On the one hand you see kids growing up faster and faster and on the other people staying younger longer in terms of mature/immature, responsibility/irresponsibility. I'm just an artist, not a sociologist, but this is my impression. The extropians talk about our being preconditioned by human history, by our 'deathist ideology'. No matter what form this takes -- from total acceptance to total denial -- it is ultimately one and the same -- we all live by reconciling ourselves to the fact that we're going to die. We know that in the West we've removed death from our sight: the institutionalisation of the sick and the elderly out of the home and so on. We avoid death. But it's funny how uncomfortable some colleagues get when I talk about issues around life extension. They don't want to live a long time. I do. I'm really curious to see where all this goes. I think your project too, the necronautical project, skirts this boundary. In an experience economy, what would be the value of a near death experience? I don't know, but I want one. And I can use art to legitimate myself having one -- and not only one but many.

TMcC: And again, you're not simulating it: you're doing it.

PP: Yes. It's not near-lethal, but there are risks involved. I could have had a heart attack. But I calculated the risk and went ahead.

TMcC: That thing about capitalism again: risk assessment. So what happened? What did you experience? What did you see?

PP: It's hard to say. Of course, people are very interested to know, and I'm interested to try to tell, and there are a number of features one can talk about. But at the same time there was a very strong sense of being beyond, beneath, below, past, the subject -- a place where no language exists.

TMcC: So was it spatial? Did you have a sense of being in space?

PP: I came back talking a lot about space. Which brings up another feature: I've never had such a strong sense of 'before' and 'after'.

TMcC: While you were in it?

PP: No, when I came out of it. It seemed like all the before-ness was a million years ago, barely remembered. It didn't even seem like my life. And another thing: the aftermath was the opposite of when one wakes up from a dream and remembers it straight away. In the beginning I could remember nothing of the experience itself. I was just amnesiac. In the weeks following I had a lot of flashbacks, but in the hours and days following I was just a blank. There was a lot of nothing. I'm still recalling more and more. It was a couple of months ago now.

RlaF: What were you using actors for?

PP: Part of the representation. I thought I'd be unconscious for a period of about an hour, and I wanted to have two people, two elderly people, having a discussion while I was lying at their feet like a sleeping dog.

TMcC: A scripted discussion?

PP: Yes.

TMcC: What were they saying?

PP: I'd rather not say. The thing is, I'd decided that what they were going to say was something I shouldn't hear.

TMcC: But you scripted it yourself?

PP: Yes. We shot the scripted texts before, in the morning, and in the afternoon we did the thing. I'd been advised to separate the two, that I'd be really susceptible to the sounds around me. The hearing's the last to go. Ketamine can be very psychologically disturbing; I've read reports of people believing that they had gone to hell. The things we'd scripted could have really hurt me. So I was trying to mitigate disturbances as much as possible. Everyone spoke quietly. But in fact things did go a bit wrong. I planned to inject intramuscularly but hit a vein, so the drug came on almost immediately. I got the needle out, then collapsed. The crew panicked. So right from the get-go, things went wrong. But they composed themselves and carried on.

RlaF: Did they face an ethical problem?

PP: The medical personnel which I tried to involve had an ethical problem but I don't think the crew did. There wasn't that much of a danger. I told them that if I vomited they had to clear my mouth and so on. Ketamine's not that dangerous. Kids in England snort it, although not many people inject it intramuscularly. It's considered addictive, which is unique for hallucinogenics. Another unique thing about ketamine is that it's completely artificial: its a molecule which is not found anywhere in nature.

(Louwrien Wijers. A Thousand Deaths: Sortie 1. 2000.)

TMcC: Were these actors dressed as angels?

PP: No, it was very secular. I had hoped to do it here in London, and had corresponded with your Techno-Chemical representative, Jamie King, who introduced me to Karl Jansen. But Jansen refused to help, so I did it in my studio in Rotterdam. It was very hard to get the drug. You'd have thought that in Holland it would be easy, but I wanted Ketalar, the injectable version. Another thing I learned: the floor made me very aware of the body image. Next time I do it I want to break up the body image. There are things you can do to achieve this. When I woke up I didn't know who or what I was. I was banging my head against the floor so as to feel my body. I was trying to bring back reality, and myself. It was unlike any other drug that I've ever experienced. Time gets seriously fucked. And it's disturbing afterwards to try to piece together what happened. We had two cameras filming: one just running in the background and one operated by the camera man. So I had two different views afterwards, and tried to reconcile those views with what little bits I remembered of my own experience.

TMcC: So it was view and overview? Metaview?

PP: Sort of, yes - or action and general registration. To go back to the Buddhist thing: Buddhism is all about death, impermanence, change. The Tibetan form is perhaps the most articulate, the most baroque, especially as reflected in the Bardo Thödol, the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

TMcC: I'm familiar with the Egyptian one, but not the Tibetan. The Egyptian one is very spatial, and very much about cryptography and passwords. I wrote an article some time back describing it as the world's first piece of software: it's about access to certain areas and the ability to perform functions and ward off certain viruses. But what's the Tibetan Book of the Dead like?

PP: You should look at Stanislav Grof's overview of Books of the Dead: Tibetan, Mayan and Egyptian. He looks at them from a psychoanalytic perspective. My own perspective on the Tibetan Book of the Dead is one of practise. A Thousand Deaths: Sortie 1 is constructed like a silent film, with intertitles; one of the last says: 'Practise Makes Perfect'.

TMcC: How many sorties do you think there'll be?

PP: I don't know. Maybe a thousand. It's a very nice way for me to work for the next few years.

RlaF: Can you dictate what actions you can perform when you're under the ketamine?

PP: That's one of the things I want to work on. The Dalai Lama talks about the state of the mind at the moment of death as being extremely important. There are precepts in Buddhism about right living, but I think it is a mistake to look at these as simply an ethical code. They're there to make sure you're in the right state of mind when the moment comes -- specially if it comes, as in Alistair Gentry's Hundred Black Boxes, out of the blue. The moment of death affords a possibility for real liberation if one recognises it. If one misses the opportunity, in other words doesn't recognise it, one has to live again, try again as a revenant, as someone undead, starting with the intermediate state, the bardo plane, which is basically what the near death experience is all about. For the Tibetans this means up to forty days of confusion and strange hallucinations before you are reborn. As you continue, the hallucinations get grosser and grosser. When you are about to be reborn, it turns very carnal. Basically, you're just watching porno movies. And the actors in the one porno movie that really grabs you are your father and mother.

TMcC: That's where Buddhism ties back in with the Western tradition: Freud and all that.

PP: It maps pretty interestingly across Lacan too. But for me, looking at that whole practise -- death, intermediate state, rebirth -- is looking at change, and how change occurs in life.

RlaF: So as an artist, these ketamine trips are analagous to other processes...

PP: Yes. There's another side: there's the balance between what the artist does trying to discover something for themselves and what the artist does trying to demonstrate or show something to others. When it comes to death this can be understood as the balance between personal death and social death. So it's interesting for me to look at the work from these two perspectives. I don't think I'm going to show myself injecting ketamine in future films; for me it's more about taking something from the one experience and putting it into the next. That's the parabolic flight aspect of it: short episodes that connect to one another.

RlaF: Parabolic flights are also very strong emotionally. People get flashbacks afterwards. Its very visceral too: your internal organs are becoming weightless during the flight.

PP: Really? I'm very interested in the body, and the body's knowledge of death. In the parabolic flights, which I understand you also film, you have the same problem, the difference between people looking at the film afterwards and the actual experience of being in zero gravity. Is it addictive too?

RlaF: The cosmonauts who came on our flight were definitely doing it to get their fix. Two of them were clearly 'fixing'.

TMcC: When I went to Alcatraz, which is now a national park, the tour guide said that many of the visitors are former prisoners. But that social aspect to your performance: that's very important. And it makes it quite traditional, too. Antigone is about social death: where they bury Polynices demarcates what is the polis, what is the space of the state, what's outside the space of laws and regulations. Then you get Addie Bundren in As I Lay Dying, or the dead man in Ionesco's Amédie, or How to Get Rid of It. There's a whole tradition there. The social aspect is what phenotypes it out. Without it it would just be solipsistic.

PP: Yes: the genotype needs the phenotype to replicate itself. The artwork replicates itself as a meme that bears repeating.

TMcC: It's giving life to the dead: that Blanchot thing.

PP: Yes, it is Death Sentence, absolutely.

TMcC: The title of that book in the original French is L'Arret de Mort. It means 'death sentence' but also 'temporary reprieve', when maybe a final appeal has been granted or something -- that moment of hiatus. Blanchot also plays a lot on the word 'pas', which means 'not' but also 'pace', 'step'. It gets very complicated. But it's about that same ultra-paradoxical economy that revolves around death, and death being the horizon of representation.

PP: And the interesting thing about this death/intermediate phase/rebirth thing is how death maps across birth. And repetition: if you don't get it right, don't worry, because you can do it better next time round. The basic idea is that this life is simply a holding room for the intermediate state ride.

TMcC: I love Giambattista Vico, the eighteenth century Italian philosopher. All this stuff in Nietzsche about eternal return, the ewige Wiederkehr, comes from Vico. That's where Joyce got the idea for Finnegans Wake, and Beckett -- all his endless repetition. But in Vico it's not a cycle like a ring; it's a spring, like a slinky-toy that you throw down the stairs. He has this term 'ricorso', which is sort of untranslatable. It's often translated as 'repetition', 'a cycle', but actually it has a legal sense, like 'recourse', 'retrial', an appeal. So it ties in with this notion of archiving, or with Beckett's plays: the characters do the same thing, going 'Here we are, again, like we were yesterday' -- which means it's not like yesterday, because yesterday they had no consciousness of yesterday being yesterday. So there's this constant self-archiving spiral. I find that an incredible structure. You can do so much with it.

PP: The difference between a circle and a spiral is that the latter exists in an extra dimension. It's good to think in n-dimensional spaces: a circle extended into the x-dimension can be a sphere, but in the x-plus-one dimension is pulled into a spiral. The image there is of accumulating some kind of energy, some kind of awareness, some kind of consciousness which essentially allows a freedom out of that.

TMcC: Exactly. When you think ontology within that kind of structure, suddenly you've got the dimensions of ethics, history, memory -- that's where all this comes in. Otherwise it's just boring. And presumably in later sorties your points of reference will be previous sorties.

PP: Yes. There are precedents in all forms of art before, but I love this process where on the one hand you can have self-containment in a small episode, but at the same time you can be promiscuous with your references. That's also what the web project Alamut is about: it's for a longer period of time. I sometimes wonder why we don't have that notion of the epic so much in our society: transgenerational cultural things.

TMcC: Maybe the epic arc has been replaced -- both as a narrative structure and a historical one. You could say it ends in Auschwitz. Maybe. Time is measured in different units than it used to be. You were talking yesterday about the clock of the long now, which ticks every hundred years and chimes every thousand.

PP: Something else: are you familiar with the idea of the singularity?

TMcC: No.

PP: It's an astrophysical term. It refers to the event-horizon around a black hole. The boundary beyond which -- from our perspective -- no light escapes, where light is pulled back. There's this guy, Vernor Vinge, a science fiction writer and physicist from the University of Southern California. Why are so many scientists writing speculative fiction? Anyway, Vinge uses the term singularity as a metaphor for some sort of horizon to human understanding. What will happen to humanity, to our society and culture, if the rate of 'accelerating change' continues? If nanotechnology happens? If strong AI happens? if we really take the implications of something like nanotechnology on board, they're enormous. Mankind would have unprecedented control over matter. A world containing man-made replicators built from atoms would completely change the human condition. We have trouble extrapolating from this sort of event -- we know the technology is coming -- but we feel how quickly it goes beyond our ken, beyond the scale of our understanding. This is the 'singularity.' It's like some kind of barrier, a windscreen on a freeway moving quickly towards us. Beyond the barrier our understanding seems to break down, our mental models collapse, like the collapse of Blanchot's sentences. Do you know project Xanadu?

TMcC: Vaguely...

PP: It's the World Wide Web as envisioned by Ted Nelson decades before the World Wide Web built by Tim Berners-Lee. It's interesting that K. Eric Drexler, the father of modern nanotechnology was involved with Xanadu. He felt that our society needed such a system in order to be able to discuss the changes that would occur in our society when things like nano arrive. You find the same issues in genetics and medicine: many people believe we're not up to speed ethically, politically, socially and so on, to be able to handle the changes that are approaching us. The coming singularity. But on the other hand I've recently started to imagine that singularities could occur behind us as well.

(Recovery. A Thousand Deaths: Sortie 1. 2000)

TMcC: So you understand them later? You create them retroactively by understanding it?

PP: You go through them, but you don't understand them at the time. It's only through memory, as you move further away from the event, that you begin to realise: my god, I just went through something, a singularity. Actually, it's not even that you think 'I went through it'; it's more that you suddenly notice its appearance somewhere behind us.

TMcC: Like an object that takes shape in the rear-view mirror?

PP: Yes. It's a force that's changing you as you pull further away from it.

TMcC: What you're doing is using quantum terms to describe the structure of memory. It's what Chris Marker's films are about: isolating singularities that get created through the act of contemplating them, like Schroedinger's cat gets killed or not killed only when he's observed.

PP: Yes: through observation and through distance. I did that thing, that little thing, and the further I go from it, the more significant it becomes.

|

![]()

![]()